From the briny seafood of the Atlantic provinces and the unique wild game of the North to the delicate fish in the waters of British Columbia and the breadbasket of the Prairies, Canada’s cuisine is as diverse as its people.

And every bit of this bounty is worth celebrating. “A timely and valuable subject,” is how Chris Johns, head judge for the Canadian Culinary Championships (CCC) and author of True North, A Taste of Prince Edward County and The Last Schmaltz, put it when asked about the topic.

As such, and in our continuing patriotic ode to Canada, we consulted chefs and culinary experts from across the country to compile a list that includes one truly special and quintessential ingredient from each province and territory.

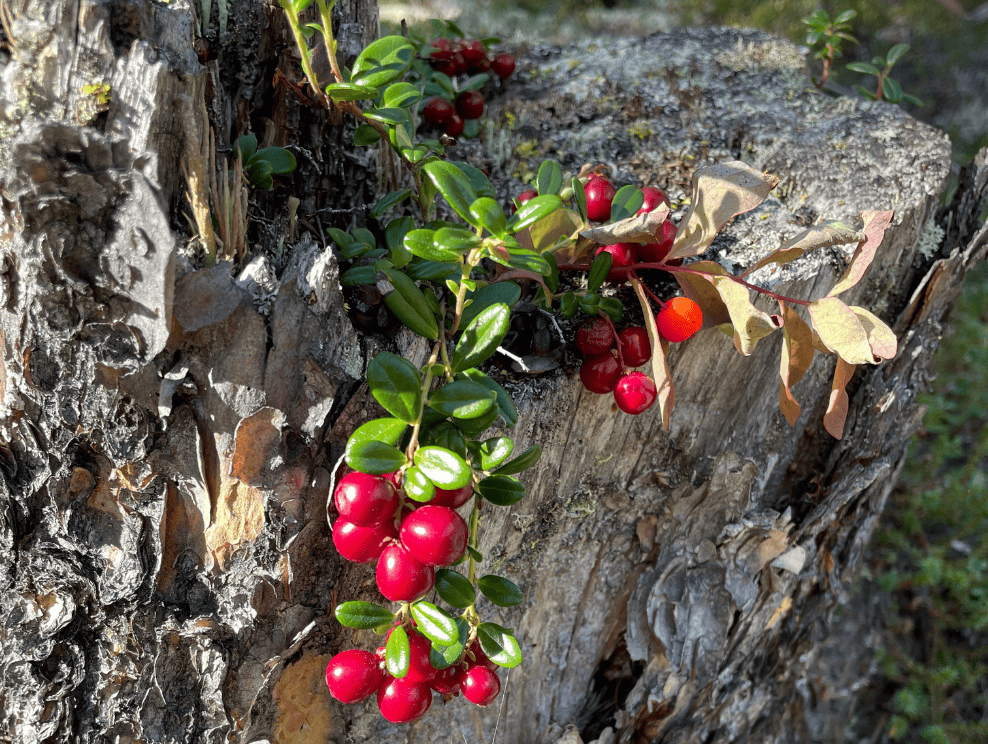

Yukon

Asked to pick just one Yukon ingredient, federal retiree Miche Genest didn’t hesitate: low-bush cranberries. Each autumn, Yukoners set out on foraging pilgrimages to collect the tart, deep red beauties. Used in breads, cakes, sauces, reductions for wild meat, chutneys, jams and pancakes, they are beloved by chefs and non-chefs alike.

“It’s a huge cultural activity to go out picking low-bush cranberries,” Genest says. “Everyone has their favourite spot.”

Northwest Territories

Johns spent his first 10 years in N.W.T. and one of his earliest memories was getting in a twin-otter sea plane to go to a remote lake to fish Arctic char. After they pulled the “absolute sea beasts,” out of the Northern waters, they built a fire on the shore, gutted, cleaned and fileted the fish. “It’s delicious — super healthy. It tastes somewhere between salmon and trout, but it's rich and to me, it feels like a very Canadian ingredient,” Johns says.

Nunavut

Trudy Metcalfe-Coe is an award-winning Inuk chef who travels across the North for cooking stints, including Qikiqtarjuaq, Nvt., this year. Her suggested ingredient is the tart akpik berry, as it’s known in her Inuk dialect, or the cloudberry as it’s known in N.L .

“People eat them as they are, or they can be made into a jam, a coulis for desserts or a compote or chutney for wild game,” Metcalfe-Coe says, comparing the colour to that of dried apricots. “They can also be baked into a pie. If they’re ripe, they don’t need much, but the less ripe ones can use some sweetness.”

British Columbia

For a B.C. ingredient, Johns names a relatively new Canadian fishery — gooseneck barnacles.

“A lot of the product is still shipped [to Spain], but restaurants in Canada and the U.S. are figuring out what these weird little monstrosities are, and just how delicious they are.” He admits that although there are strict safety regulations in Canada, part of the romance is that fishers are “risking life and limb” to harvest them.

Johns serves them simply: boiled in salted water briefly and then eaten with a squeeze of lemon, if that.

Alberta

Doreen Prei, who represented Edmonton in the CCC, named farro, the oldest cultivated grain in the world, as her quintessential and special Alberta ingredient.

“This is the hardest question ever,” Prei says. “Alberta is such an amazing province, but if I had to choose one, it would be farro because it’s interesting and extremely versatile. I have a tattoo of farro.”

She cooks it as risotto, porridge, as a base for hearty salads and she uses it as an intriguing flour to add to pancake and pizza dough. “It’s also nice for bread.”

Saskatchewan

Taszia Thakur, of Calories Restaurant, who represented her province in the CCC, chose lentils because Canada is the world's largest producer and exporter of lentils, and Saskatchewan grows approximately 90 per cent of them. Her favourites are Beluga and du Puy lentils.

On her menu, you might find a Beluga lentil “pilaf” served with stuffed duck; smoked duck breast with braised du Puy lentils and crispy lentils in a pasta featuring fiddleheads, morels, gnocchi and chive beurre blanc.

Manitoba

Mandel Hitzer, chef and owner of deer + almond restaurant, which is 39th on Canada’s 100 Best restaurants list, named greenback pickerel, which speaks to Manitoba’s cabin and fishing culture. He calls the Manitoba fresh water fish “sacred.”

“It’s a lifestyle,” he says, noting that when they went fishing, they carried a cast iron pan, oil, flour and beer. “You fish it, and then clean it, build a little fire and fry it in beer batter.” When he’s being cheffy, he cuts off the gills and flours and fries them. “You get the most succulent-tasting part of the fish, and the fin becomes like a potato chip,” he says.

Ontario

Johns says one of his favourite ingredients “ever, and for always” is wild ramps, also known as wild garlic, which, he stresses, has to be respectfully foraged — otherwise it won’t come back.

“It’s this lovely, soft, deep green leaf with a gentle garlic taste,” he says. “You can make pesto, you can purée it and add it to pasta dough, and the bulb ends are delicious pickled. You can also add them to pasta sauce. It’s such an elegant ingredient and gorgeous in colour.”

Quebec

François-Emmanuel Nicol, chef at Quebec’s City’s la Tanière, and the bronze-medal winner at the CCC, named snow crab.

“What makes snow crab so special for me is that it’s one of the first signs of spring in Quebec,” Nicol says. “After a long winter, the arrival of snow crab is a cause for celebration.”

He says its “sweet, delicate flavour is unlike anything else, and it represents the start of a new season of culinary possibilities.” He serves it simply and always enjoys a spring ritual of snow crab with mayo, baguette and a glass of white wine on the patio with his mom.

New Brunswick

Jordan Holden, chef at Moncton’s Atelier Tony, who won silver at the CCC, named fiddleheads as N.B.’s ingredient.

“One of my favourite things to do is forage,” he says. “Foraging for ingredients and bringing them back to my kitchen makes a dish a lot more meaningful. Fiddleheads are the first sign that foraging season has begun.”

He uses them simply to preserve their delicate flavour — sautéed with butter, pickled, steamed, put into pasta or turned into a soup.

Nova Scotia

Heather Townsend, co-owner of Edna Restaurant in Halifax, nominated Nova Scotia oysters.

“They tend to have a brinier, more complex flavour compared to P.E.I. oysters, with a crisp, minerally finish that reflects the rocky, nutrient-rich environment they grow in,” she says. “They feel like a true expression of the place — wild, untamed and full of character.”

Edna serves them raw with mignonette, lemon, and house-made hot sauce; fried with a house-made aiolis or baked with taleggio cream, fried leeks and sea truffle.

Prince Edward Island

Michael Smith, celebrity chef and owner of the Inn at Bay Fortune in P.E.I., is a big fan of foraging and chose wild watercress.

“Foraging truly connects us to the seasons and microclimates of the island,” Smith says. “I forage watercress daily in a variety of local streams.”

He says it’s the most nutritiously dense food in the world and he includes it nightly in his salad bowl at his multi-course dinner — the Feast — at the inn. He says it’s “delicious, fresh and snappy and will stay alive for weeks in a bouquet of water in the fridge.” He likes it in a light lemon vinaigrette and served with your favourite fish.

Newfoundland and Labrador

Chef Nicholas Walters of St. John’s Merchant Tavern and the province’s representative at CCC, names cod as Newfoundland’s special ingredient.

“Cod has a beautiful mild flavour and a flaky texture that lends well to many applications,” Walters says. “I like to simply pan-fry it with brown butter and finish it with a nice beurre blanc. I also love how it pairs with a classic onion soubise. Traditionally, we fry it with a crispy beer batter and serve it with tartare sauce.”